Semi-Markov models with msmbayes

Christopher Jackson chris.jackson@mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk

2025-08-28

Source:vignettes/semimarkov.Rmd

semimarkov.RmdNon-Markov models have previously been difficult for intermittently observed data, since we do not know the times of entry to the states. For some transition structures, we may not even know whether or not any particular transition took place within an interval between observations. Hence it can be hard to discern how the hazard of transition out of a state depends on the time spent in that state.

msmbayes makes these models easier to use. It can fit

multi-state models where the sojourn distribution in any state has a

special two-parameter distribution. This relaxes the Markov assumption,

producing a semi-Markov model, where the transition rate out of a state

depends on how long the individual has spent in the state. The sojourn

distribution used for these models is a phase-type approximation to

a shape-scale distribution, The phase-type approximation idea was

introduced by Titman, 2014.

msmbayes introduces an easier way to obtain the

approximation, and makes these models accessible for the first time.

Full details will be given in a forthcoming paper.

msmbayes can also fit phase-type models directly - see

a separate vignette about these.

msm can also do this with two-phase models. However these

are awkward to use in practice for intermittently observed data. They

have several parameters, which are hard to interpret, and computation

tends to suffer from poor identifiability. By contrast, phase-type

approximations to shape-scale distributions have only two parameters,

and are based on well-understood parametric distributions.

Phase-type shape-scale distributions

The distribution has two parameters: shape \(a\) and scale \(b\). The probability distribution function is defined by

\[ F(x | a, b) = F_p(x | \boldsymbol{\lambda} = b \mathbf{h}(a)) \]

where \(F_p(x |

\boldsymbol{\lambda})\) is a phase-type distribution (with 5

phases by default) and vector of transition rates \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}\). The shape and scale

are mapped to the phase-type transition rates through a function \(\mathbf{h}()\), determined so that the

first three moments of the phase-type distribution are the same as those

of the Weibull or a Gamma, for a wide range of shape parameters. This

function is pre-determined (using the formulae from Bobbio et al.) and

stored in the msmbayes package. A default of 5 phases is

used. This process will be described more formally in a forthcoming

paper, but for now, the code is in the package source

(phaseapprox branch).

Covariates can be applied to the scale parameter \(b\), as a linear model on \(\log(b)\), giving an accelerated failure time model.

Additional assumptions are needed if there are multiple alternative states \(s\) that an individual can transition to immediately on leaving a state \(r\) that has a phase-type approximation. In

msmbayes, this transition is governed by a constant “next state” probability \(\pi_{rs}\), as is done in Titman, 2014. This assumes that the transition probability does not depend on the length of time spent in state \(r\) (the supplementary material to Titman, 2014 discusses more flexible alternatives).Covariates can also be applied to \(\pi_{rs}\) via a multiplicative model on the odds of transition.

Implementation in msmbayes

This vignette gives a demonstration of using semi-Markov models with

phase-type shape-scale distributions in msmbayes, based on

an artificial dataset.

Note: this vignette should not be used literally as a step-by-step recipe for an applied analysis. It is intended to demonstrate the range of functions available in the package and how to use them. An applied analysis should take account of the research question, including thoughtful choice of priors, computing appropriate outputs of interest, model checking and comparison.

Specifying a basic semi-Markov model

To specify the states given a semi-Markov model, specify the

pastates argument to msmbayes, say

pastates=2 if this is state 2, or

pastates=c(1,2) if both states 1 and 2 are semi-Markov.

To start with, we fit a two-state infection model to the basic data

infsim2 from the Examples

vignette. This is now made into a semi-Markov model. We compare a model

with the default Gamma approximation (in both states) to a model with a

Weibull for both states (setting the pafamily

argument).

If there is more than one state given a semi-Markov model, different distributions can be used for different states, e.g

pastates=c(1,2), pafamily=c("weibull","gamma").

library(msmbayes)

Q <- rbind(c(0,1), c(1,0))

drawsg <- msmbayes(data=infsim2, state="state", time="months", subject="subject",

pastates=1:2,

Q=Q, fit_method="optimize")

drawsw <- msmbayes(data=infsim2, state="state", time="months", subject="subject",

pastates=1:2, pafamily="weibull",

Q=Q, fit_method="optimize")In this vignette, the Bayesian models are all fitted using posterior mode optimisation and Laplace approximation (MCMC would be safer - avoiding the risk of finding a local optimum or mis-estimating uncertainty - but a lot slower).

Summarising shape parameters

Shape parameters around 1.0 (exponential distribution) are supported for both states 1 and 2, indicating no evidence that the model is semi-Markov. Indeed, the data were simulated with exponential sojourn distributions.

Note that the summary method for msmbayes

objects compares the posterior distribution with the prior. The prior is

summarised as a string displaying the median and 95% credible interval,

or an rvar object containing a full posterior sample. See

the main msmbayes vignette for an

explanation of the rvar format used in the column

“posterior” and how to summarise it.

summary(drawsg, pars="shape")## # A tibble: 2 × 6

## name from posterior mode prior_string prior

## <chr> <chr> <rvar[1d]> <dbl> <chr> <rvar[1d]>

## 1 shape 1 1.1 ± 0.38 1.02 1.0 (0.38, 2.66) 1.1 ± 0.6

## 2 shape 2 1.0 ± 0.12 1.00 1.0 (0.38, 2.66) 1.1 ± 0.6

summary(drawsw, pars="shape")## # A tibble: 2 × 6

## name from posterior mode prior_string prior

## <chr> <chr> <rvar[1d]> <dbl> <chr> <rvar[1d]>

## 1 shape 1 1.0 ± 0.18 1.04 1.0 (0.61, 1.63) 1 ± 0.26

## 2 shape 2 1.1 ± 0.25 1.13 1.0 (0.61, 1.63) 1 ± 0.26Choice of priors

When fitting these models, we used the default prior distributions. For the shape parameters, the defaults are chosen to give flexible and numerically stable model families based on the Weibull and Gamma. For example, the default SD of the Weibull distribution was chosen to rule out values for the shape parameter lower than about 0.6, for which the phase-type approximation deviates from the Weibull and becomes increasingly unstable as the shape decreases.

In a real application, instead of accepting the defaults, a better approach to specifying priors is to draw random samples from priors and transform these to more interpretable quantities (e.g. the mean sojourn time) to determine what priors a given choice implies for those interpretable quantities - starting with the defaults, and modifying by trial and error if necessary.

A more detailed illustration of specifying priors informed by background information will be given in the appendix of a forthcoming paper.

Comparing the Gamma and Weibull

We can roughly compare the fit of these models through their likelihoods. The mode of the log posterior (i.e. the maximum penalised likelihood, with the priors considered as a penalty) essentially measures in-sample predictive ability. For a multi-state model, that is the ability to predict an individual’s next observation given their current and previous observations. Since the two models being compared here have the same number of parameters, and the priors are of similar strength, any improvement in the likelihood would suggest better generalisability. In this case, the maximum log posteriors for these two models are very similar.

(Cross-validation would be a better way of comparing, but it is unclear how that might be set up with an intermittently-observed multistate model)

loglik(drawsg)## name posterior mode

## 1 loglik -143.7 ± 2.21 -142.235930

## 2 logprior -5.8 ± 0.77 -5.399696

## 3 logpost -149.5 ± 2.29 -147.635626

loglik(drawsw)## name posterior mode

## 1 loglik -144.8 ± 9.2 -142.200516

## 2 logprior -4.7 ± 1.4 -3.886514

## 3 logpost -149.5 ± 10.0 -146.087029Sojourn distribution

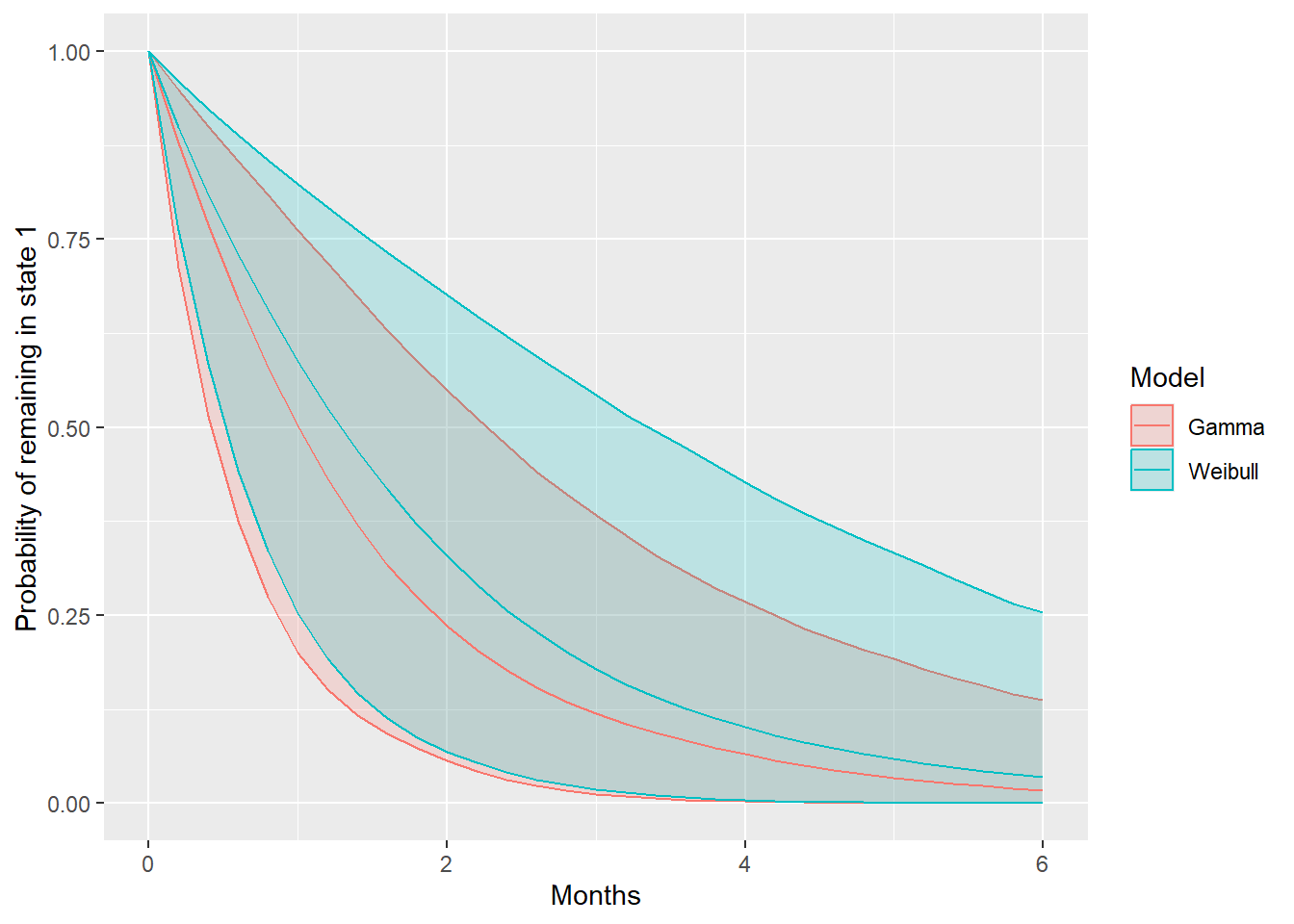

The function soj_prob() computes the probability of

staying in a given state, at a sequence of times, from a fitted

msmbayes() model. It can be used to plot a kind of

“survival curve” for the sojourn distribution in a state. In this case,

there is little difference between the Weibull and Gamma distributions,

and a lot of uncertainty.

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

t0 <- seq(0, 6, by=0.2)

spg <- soj_prob(drawsg,state=1,t=t0) |> mutate(Model="Gamma")

spw <- soj_prob(drawsw,state=1,t=t0) |> mutate(Model="Weibull")

sp <- rbind(spg, spw)

summary(sp) |>

ggplot(aes(x=time, y=median, col=Model)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=q5, ymax=q95, fill=Model), alpha=0.2) +

geom_line() +

xlab("Months") + ylab("Probability of remaining in state 1")

The mean of the sojourn distribution, the mean time to the next

transition on entry to a state, is given by mean_sojourn().

The mean of the phase-type approximation should agree with the mean of

the distribution that it was based on, since the approximation was

designed to match the first three moments. This is verified here for the

Gamma distribution, which has mean defined by

shape x scale.

mean_sojourn(drawsg)## # A tibble: 2 × 3

## state posterior mode

## <int> <rvar[1d]> <dbl>

## 1 1 1.61 ± 0.78 1.51

## 2 2 0.29 ± 0.14 0.261

shape <- summary(drawsg, pars="shape")

scale <- summary(drawsg, pars="scale")

shape$posterior * scale$posterior## rvar<4000>[2] mean ± sd:

## [1] 1.61 ± 0.78 0.29 ± 0.14Specifying a semi-Markov model with covariates

We now extend the Gamma model to include a covariate (binary, representing sex) on the scale parameter for the distribution in both states. The log likelihood hardly changes, as we might expect, as there was no covariate effect assumed when the data were simulated, so this model includes a lot of extra unnecessary parameters.

The prior for the shape parameter in this example is tightened to

support a slightly smaller range of values (up to

exp(2*0.4) = 2.2). With the default prior SD of 0.5, the

optimisation fails to converge, likely due to weak identifiability. We

see in the posterior summary that in fact the posteriors for the shape

parameters are similar to the priors, indicating weak information in the

data about these parameters.

drawsc <- msmbayes(data=infsim2, state="state", time="months", subject="subject",

pastates=1:2,

priors = list(msmprior("logshape", mean=0, sd=0.4)),

covariates = list(scale(1) ~ male, scale(2) ~ male),

Q=Q, fit_method="optimize")

loglik(drawsc)## name posterior mode

## 1 loglik -151 ± 21 -142.13004

## 2 logprior -12 ± 1 -11.02586

## 3 logpost -163 ± 21 -153.15590

summary(drawsc, pars = "shape")## # A tibble: 2 × 6

## name from posterior mode prior_string prior

## <chr> <chr> <rvar[1d]> <dbl> <chr> <rvar[1d]>

## 1 shape 1 1.1 ± 0.38 1.04 1.0 (0.46, 2.19) 1.1 ± 0.45

## 2 shape 2 1.0 ± 0.12 1.000 1.0 (0.46, 2.19) 1.1 ± 0.45Time acceleration factors

The covariate effects in this model can be summarised as “time acceleration factors”. In this case, their posterior distributions cover a very wide interval, indicating a lack of information in the data and no evidence for an effect in either direction.

Note the use of the

summary()function on the object returned bytaf(), which applies a user-specified summary to theposteriorcolumn of this object, as explained here). Note alsotaf(...)is an alternative tosummary(..., pars="taf").

taf(drawsc)## from name posterior mode

## 1 1 male 20 ± 101 2.768362

## 2 2 male 18 ± 79 2.556254## from name mode 2.5% 50% 97.5%

## 1 1 male 2.768362 0.05896570 2.953502 157.0297

## 2 2 male 2.556254 0.05309879 2.614734 145.5197Outputs from fitted models by covariates

All standard multistate model outputs are supported for semi-Markov models as for Markov models.

Transition intensities (

qdf(),qmatrix()) for semi-Markov models are only defined on the latent space of “phases” rather than observable states.Transition probabilities over any time interval (

pmatrixdf(),pmatrix()) are available on the space of observable or latent states. For observable states (the default) this describes the probability of transitioning to any phase of each “destination” state (summing over phases within a state), for a person in the first phase of each “starting” state.Mean sojourn times

mean_sojourn(), or the total length of staytotlos()can be produced for either the observable states or the latent phases.

For example, the total length of time spent in each observable state,

over 12 months, is computed here for two different covariate values (men

and women). If nd is not supplied, the output is returned

for covariate values of zero.

nd <- data.frame(male=c(0,1))

totlos(drawsc, t=12, new_data=nd)## # A tibble: 4 × 4

## # Groups: state [2]

## state posterior male mode

## <int> <rvar[1d]> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 10.3 ± 0.37 0 10.3

## 2 1 10.2 ± 0.45 1 10.2

## 3 2 1.7 ± 0.37 0 1.66

## 4 2 1.8 ± 0.45 1 1.81Or for a standard population whose distribution matches the observed

distribution of covariates in the data frame nd, here 50%

men and 50% women:

totlos(drawsc, t=12, new_data=standardise_to(nd))## # A tibble: 2 × 3

## state posterior mode

## <int> <rvar[1d]> <dbl>

## 1 1 10.2 ± 0.41 10.2

## 2 2 1.8 ± 0.41 1.77We may also break down the total length of time spent in each of the five latent phases that comprise a stay in state 1 or state 2, though this is only of academic interest. These are the states of the hidden Markov model that is used to implement the semi-Markov model.

totlos(drawsc, t=12, states="phase")## # A tibble: 10 × 5

## state posterior mode stateobs statephase

## <chr> <rvar[1d]> <dbl> <int> <int>

## 1 1p1 8.441 ± 1.207 10.1 1 1

## 2 1p2 0.513 ± 0.311 0.0643 1 2

## 3 1p3 0.472 ± 0.280 0.0629 1 3

## 4 1p4 0.431 ± 0.255 0.0614 1 4

## 5 1p5 0.393 ± 0.238 0.0600 1 5

## 6 2p1 1.607 ± 0.358 1.66 2 1

## 7 2p2 0.037 ± 0.029 0.0000000518 2 2

## 8 2p3 0.036 ± 0.028 0.0000000509 2 3

## 9 2p4 0.036 ± 0.028 0.0000000500 2 4

## 10 2p5 0.035 ± 0.027 0.0000000492 2 5Semi-Markov models with competing risks

This is based on the dataset illdeath_data, a simulated

dataset with three states representing health, illness and death. Death

is allowed from either living state, and no recovery from the illness is

assumed.

State 1 is given a semi-Markov model with pastates.

There are “competing risks”, since on leaving state 1, an individual can

either get the illness or die without the illness. The binary covariate

“sex” modifies both the scale parameter for the sojourn time in state 2

(illness), the chance of moving to 3 (rather than 2) on leaving 1, and

the rate of transition from illness to death.

Note If the state, time and subject variables are called “state”, “time”, and “subject”, we do not need to name them explicitly in the call to

msmbayes().

Qid <- rbind(c(0,1,1), c(0,0,1), c(0,0,0))

draws <- msmbayes(data=illdeath_data, pastates=1,

covariates = list(scale(1) ~ sex,

rrnext(1,3) ~ sex,

Q(2,3) ~ sex),

Q=Qid, fit_method="optimize")This model is a combination of a semi-Markov model for the transition out of state 1, and a Markov model for the transition out of state 2, with a phase-type approximation and exponential sojourn distributions respectively.

Summarising covariate effect parameters

The effects of covariates on progression are represented differently for each of these states. For the risk of death from illness, the covariate effect is a hazard ratio.

summary(draws, pars="hr")## name from to posterior mode prior_string prior

## 1 hr(sexmale) 2 3 6.6 ± 6.6 4.782825 1 (0, 3.2e+08) 4.3e+11 ± 2.2e+13

## 2 hr(sexmale) 2 3 6.6 ± 6.6 4.782825 1 (0, 3.2e+08) 4.3e+11 ± 2.2e+13For a person in state 1, without the illness, there are two aspects of the covariate effect.

A time acceleration factor

taf, representing the effect of time on the length of stay in state 1. A biggertafspeeds up time, so that an effect size of 2 halves the expected time to the next transition. For the exponential distribution, this parameter has the same interpretation as the hazard ratio.The multiplicative effect

rrnexton the relative risk of death without the illness, relative to a “baseline” risk of getting the illness.

## name from to posterior mode prior_string

## 1 taf(sexmale) 1 NA 2.6 ± 1.9 2.01522152 1 (0, 3.2e+08)

## 2 rrnext(sexmale) 1 3 2174.9 ± 68510.3 0.05788637 1 (0, 3.2e+08)

## prior

## 1 4.3e+11 ± 2.2e+13

## 2 4.3e+11 ± 2.2e+13Summarising outputs by covariates

As covariates may influence the progression through the multi-state system in many ways, how we build and summarise the model will depend on the research question.

A useful general approach is compute an outcome of interest and

compare it between different covariate values. As an illustration, in

this model, suppose we are interested in the total time spent alive over

24 months for a person at the start of the study. First this is computed

for each covariate category to be compared (using

standardise_to() as above, if necessary, to marginalise

over other covariates).

tl <- totlos(draws, t=24, new_data = data.frame(sex=c("male","female")))

tl## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## # Groups: state [3]

## state posterior sex mode

## <int> <rvar[1d]> <chr> <dbl>

## 1 1 1.31 ± 0.40 female 1.28

## 2 1 0.85 ± 0.55 male 1.16

## 3 2 0.72 ± 0.48 female 0.648

## 4 2 0.22 ± 0.17 male 0.293

## 5 3 21.96 ± 0.62 female 22.1

## 6 3 22.93 ± 0.65 male 22.5Posterior samples are then extracted for the time in state 1 and the

time in state 2 separately, for men and women separately.

tl_12_male (and tl_12_female) will then

comprise two rvar objects.

tl_12_male <- tl |> filter(state %in% 1:2, sex=="male") |> pull(posterior)

tl_12_female <- tl |> filter(state %in% 1:2, sex=="female") |> pull(posterior)

tl_12_male## rvar<4000>[2] mean ± sd:

## [1] 0.85 ± 0.55 0.22 ± 0.17The posterior samples for state 1 and state 2 are added together to

give the posterior sample for the time spent alive. This is done for

women and men separately. Note rvar_sum is needed for this,

not the standard

Finally we obtain a posterior sample tl_diff for the

difference in the expected time spent alive for men and women.

Note:

rvar_sum()from theposteriorpackage is needed to add the “random variables” represented by rvar objects, producing a random variable representing their sum. The base Rsum()function would collapse the samples inside the rvar objects to produce a scalar, which is not what we want here.

A null hypothesis test for whether an effect is “significant” does not have a direct analogue in Bayesian analysis. Instead I would recommend summarising the posterior distribution of a quantity of interest. This might be done in different ways, e.g. as a 95% credible interval, or a posterior probability of exceeding a value of practical interest (e.g. 0, or a clinically important value):

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## variable `2.5%` `50%` `97.5%`

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 tl_diff -0.656 0.893 2.82

mean(tl_diff > 0)## [1] 0.8735